1543: First printing of Copernicus’ On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres [44]

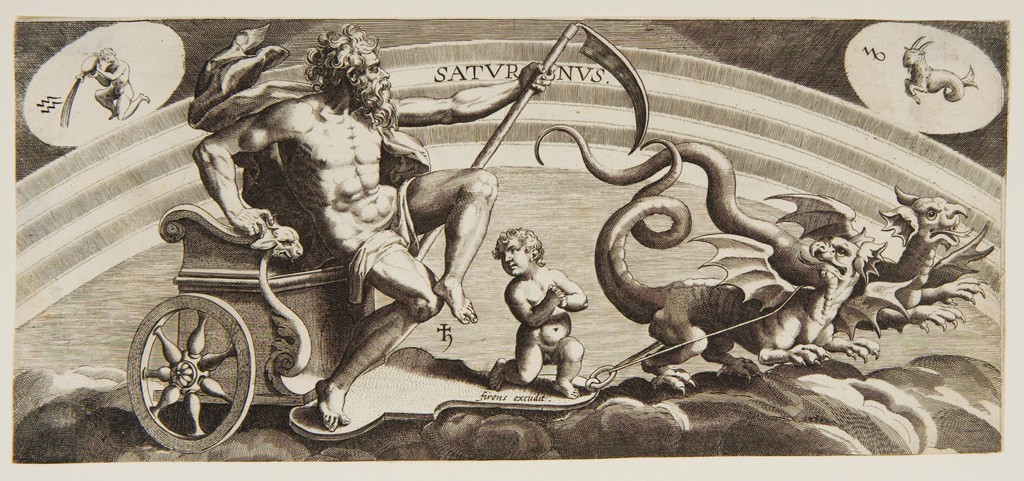

Art Piece: The Planets: Saturn, Petrus Firens, 17th Century [142]

Paper: Long-term integrations and stability of planetary orbits in our Solar system [82]

With many still significantly believing in the Creation myths presented in the Bible, the 1500s were also a time when more individuals wanted to better understand the more specific circumstances related to our place in the cosmos. People like Nicolaus Copernicus aimed to understand our celestial neighborhood better, with both Copernicus and the Renaissance as a whole representing a paradigm shift [75] between the Dark Ages and the rebirth of widespread intellectualism and scientific curiosity. With the invention of the more-modern telescope not having occurred yet — Galileo would invent one of the first models with greater-than-before magnification of the skies in 1609 [174] — Copernicus was already starting from a place of scientific difficulty. Without the wonderful tools we have today, like Harvard’s Science Center Observatory [179], making scientific and astronomical discoveries were most likely difficult to do during Copernicus’ time. However, despite these difficulties, Copernicus and many of his Renaissance contemporaries were still able to develop ideas that are still discussed and debated today, representing a significant paradigm shift. Notably, in Copernicus’ On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, Copernicus argued [135] that the Sun, instead of the Earth, is at the center of the universe, and that the Earth rather moves around the Sun. Copernicus also presented the idea that the universe and the cosmos were all interconnected within an integrated system, rather than these heavenly spheres acting in isolation, separate from one another. We now know this to be true, but in Copernicus’ time, this was a more revolutionary and new idea, creating ripples across the intellectual world at the time. These ideas about the orbits of the planets also influenced art as well, with a piece that exemplifies many of Copernicus’ ideas being this one, created in the 17th century. Entitled “The Planets: Saturn,” [142] this piece depicts Saturn, once the ruler of the other Gods and the cosmos in his chariot, appearing powerful and commanding others. Though this piece shows Saturn as secure and full of strength, it is also a precursor to what will come next in the context of the mythology — much like how Copernicus and his contemporaries’ astronomical ideas shifted the scientific paradigm and caused a revolution in how people understood the cosmos, In Greek/Roman mythology, Zeus/Jupiter also causes a revolution amongst the Gods, usurping his father Saturn to become king of the Gods himself instead. This highlights how art can be a way to represent changing times, especially changing scientific contexts and ideas. A paper [82] that also builds on Copernicus’ work is the one above, which discusses the“long-term numerical integrations of planetary orbital motions over 10^9 -yr time-spans including all nine planets” — in other words, this paper looks at the orbits of the nine planets over a long time span, analyzing any possible changes in these orbits through the life of the cosmos and our solar system. This work is very similar to Copernicus’, as it explores planetary orbits. Moreover, this work would also not even have been possible if not for the foundation that Copernicus and others had laid, showing the far-reaching after-effects of Copernicus’ paradigm shift.